Comparison 18: Dangers

This article is about section three of chapter two of The Art of War. It compares the dangers of various competitive strategies. It references the I-Ching, which is twice the age of The Art of War and was the foundation of some of its thinking.

The I Ching is known as the Book of Changes. It describes sixty-four hexagrams or “conditions” and the changes that convert one condition to another. Each hexagram is made up of two trigrams of three lines. These lines are either solid (yang) or broken (yin). “Yin” is advancing, the symbol of change and visibility. In business, think sales and marketing. “Yang” is the symbol of defense, stability and secrecy, using our existing position to get our resources. Think maintenance and trade secrets.

Each hexagram contains two trigrams from the eight sides of the Bagua (the “eight ways”). Sun Tzu’s Bagua is different than the traditional Chinese version. Its center is what we call Mission. Its primary compass points are “climate” (up), “ground” (down), “command” (right), and “methods (“left). The other compass points are the four types of ground (plains, rivers, marshes, and mountains). There are sixty-four hexagrams because each of the eight trigrams is used on the top and the bottom of each one. Eight times eight is sixty-four. Some of these “maps of meaning” are explored in my book, The Art of War and Its Amazing Secrets.

Type of Advance

Below is my translation of the Chinese that begins this section. This first stanza predicts the costly dangers of advancing our competitive positions.

The nation impoverishes itself shipping to troops that are far away.

Distant transportation is costly for hundreds of families.

Buying goods with the army nearby is also expensive.

High prices also exhaust wealth.

If you exhaust your wealth, you then quickly hollow out your military.

Military forces consume a nation’s wealth entirely.

War leaves households in the former heart of the nation with nothing

The Art of War, Chapter 2, Section 3, Line 1-7

Competitive efforts that attempt to build up our positions by expansion are costly. Transportation, opening new offices, and training a whole new group of people are all costly. Growing and advancing in the same location is also costly in a different way. If the city is too small, we must compete for local customers, suppliers, and employees. Larger cities are also expensive because of the costs of working there. The larger the city, the more office space, housing, and food costs. Employees need more pay. These higher prices also drain our resources.

When our excess resources run low, we have only two choices. We can give up on advancing our position until we build up more resources. The other alternative is to gamble on our growth, hoping it will pay off before we go broke. We can see these “households” being emptied today in most American cities where retail, office spaces, apartments, and houses are increasingly unoccupied from going broke

This brings us to our first reference to the I Ching:

War destroys hundreds of families.

Out of every ten families, war leaves only seven.

The Art of War, Chapter 2, Section 3, Line 8-9

This is an “easy” translation of the last line, but most translators ignore it entirely because they don’t understand it. It is a reference to the I Ching.

I Ching’s First Line of Advice

A transliteration of the Chinese characters of this line says:

<Ten> <go> <this> <seven, >

The Art of War, Chapter 2, Section 3, Line 9

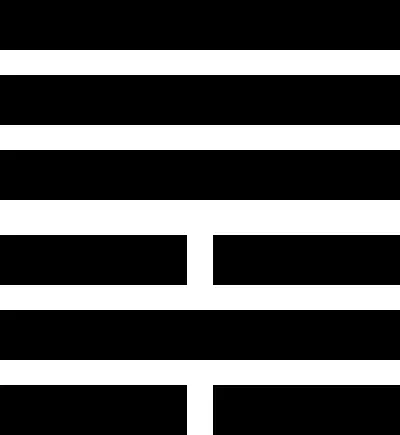

This means that Hexagram Ten is changing to Hexagram Seven.

Hexagram Ten below) is called “steps” or “tread carefully.” Its general advice is to advance in small steps. The three lines(trigram) on top mean “climate.” The bottom trigram is “marsh,” one of the four types of ground, and the one where footing is uncertain.

Ten changes into Seven. Hexagram Seven is called “Army.” but it isn’t an army of aggression.

Notice all the broken, defensive lines, with only one solid, aggressive one. This is “ground” over “river.” The “ground” is the “place” of our position. “River” is the aspect of the ground that is fluid. The army is needed because situations are naturally fluid.

Advice comes from changing the “steps” into “army.” Five lines are changed in doing this from the bottom up. The change in the foundation means that we must use proven methods and not get creative. While there are unknowns in our situation, the tried and true is the best strategy. The next line means that when the possibilities of failure exist, we must move cautiously. The third means group consensus is dangerous so a clear vision of a commander is needed. The fourth means that when confronted with opposition, there is no shame in retreat. The first is that a series of small setbacks will be hard to avoid. The final line means that we must look carefully at the character of the people we rely upon.

All these predictions are in this one line and form much of the basis for Sun Tzu’s military philosophy.

I Ching’s Second Line of Advice

The second staza here warns about the costs of failure.

War destroys hundreds of families.

Out of every ten families, war leaves only seven.

War empties the government’s storehouses.

Broken armies will get rid of their horses.

They will throw down their armor, helmets, and arrows.

They will lose their swords and shields.

They will leave their wagons without oxen.

War will consume sixty percent of everything you have.

The Art of War, Chapter 2, Section 3, Line 8-15

The point here is that failure in an advance is even more costly than advancing. The transliteration of the last line says:

<Ten> <go> <this> <six>

The Art of War, Chapter 2, Section 3, Line 15

This explains why Sun Tzu teaches “winning without conflict.” Here, the transformation is again from Hexagram Ten but now it becomes to Hexagram Six. Hexagram Six is called "Conflict." It advises that conflict is best avoided because it creates more costly setbacks. There are times when a "cautious halt" can be far more powerful than the most aggressive attack. It combines the top trigram, “climate,” from “Steps” with the bottom trigram “river” of “Army.”

“Steps” changing into “Conflict," involves only one line. It is an easy change, a slippery slope. The change is in the base of the figure, from a solid line to a broken one, the partly solid and visible dangers of a marsh with the fluid and hidden dangers of the river.

The message in this change is that we must use proven methods and not get creative. While there are uncertainties in small steps, sticking to what is solid and better seen is the best strategy in advancing. Small steps should never lead us into a river. They certainly can’t get us out.